Blanching is a basic kitchen technique used to briefly cook food in boiling water, then quickly stop the cooking. It is often used in vegetable preparation, both in home kitchens and in professional kitchens.

Home cooks encounter blanching when recipes mention terms like “parboil” (partially cook in boiling water), “pre-cook,” or “shock in ice water” (suddenly cool in ice water to stop cooking). It’s commonly used before sautéing, freezing, roasting, or adding vegetables to composed dishes.

Understanding blanching helps cooks control color, texture, and flavor rather than react after vegetables turn dull, mushy, or unevenly cooked.

At its core, blanching is about preparation and control — not fully cooking food, but setting it up to perform better later.

What Blanching Actually Means

Blanching means briefly exposing food — most often vegetables — to rapidly boiling water, then stopping the cooking process immediately.

The goal is not to cook the ingredient through, but to apply enough heat to trigger specific internal changes while preserving structure.

Three elements define blanching:

- Short exposure to heat

The food is heated just long enough to affect the exterior and surface structure, not the center. - High-temperature water

Boiling water delivers fast, even heat, allowing controlled changes without prolonged cooking. - Rapid cooling to halt cooking

Once removed from the heat, cooking must stop immediately to prevent carryover softening and color loss.

Blanching creates an in-between state: the ingredient is no longer raw, but not yet fully cooked or ready to eat.

Its purpose is partial cooking and structural adjustment, not tenderness or doneness.

During blanching, vegetables begin to relax, bright pigments become more visible, and harsh raw flavors soften. At the same time, the interior remains firm, allowing the vegetable to hold its shape during later cooking.

Because of this, blanching changes how vegetables behave afterward. Blanched vegetables cook more evenly, finish faster, retain better color, and respond more predictably to methods like sautéing, roasting, freezing, or reheating.

Understanding blanching as a preparatory technique — not a finishing one — helps cooks decide when it adds value and when it isn’t necessary.

Why This Matters in Cooking

Blanching matters because it changes how vegetables behave during the rest of the cooking process. When used intentionally, it improves flavor clarity, texture control, timing, and overall decision-making at the stove.

Flavor

Raw vegetables often carry sharp, grassy, or bitter notes that dominate when heated directly in a pan or oven.

Blanching softens these flavors before the final cooking begins.

- Harsh vegetal aromas mellow quickly with brief heat exposure

- Bitterness in greens such as broccoli rabe, kale, or mustard greens becomes more balanced.

- Natural sweetness becomes more noticeable once raw notes are reduced.

The result is a cleaner vegetable flavor that integrates better with fats, sauces, and seasonings instead of competing with them.

Texture

Many vegetables have dense fibers or rigid cell structures when raw. If cooked directly, the exterior often softens before the interior has time to relax.

Blanching begins this structural shift early.

- Fibers soften without collapsing.

- Vegetables bend rather than snap.

- Surfaces cook evenly during later high-heat methods.

This prevents common problems such as:

- Mushy outsides with firm centers

- Uneven browning

- Vegetables breaking apart under stirring

When followed by quick finishing methods, blanching helps preserve firmness and snap rather than destroying them.

Timing

One of blanching’s biggest advantages is the control it offers over cooking time.

Because vegetables are partially cooked ahead of time:

- Final cooking happens faster.

- Heat exposure becomes shorter and more precise.

- Vegetables can be added later without falling behind.

This is especially useful when coordinating multiple components.

Blanching allows vegetables, proteins, and sauces to finish together instead of forcing one element to wait while another catches up.

It turns cooking from a race into a sequence.

Confidence

Blanching reduces uncertainty.

Instead of guessing whether vegetables will soften in time, cooks begin the final stage knowing the ingredient is already halfway prepared.

This leads to:

- Fewer last-minute adjustments

- Less overcooking from panic heat

- Clearer decision-making during service or plating

Rather than reacting to what’s happening in the pan, blanching allows cooks to respond with intention.

That sense of control is often what separates stressful cooking from calm, consistent results.

How It’s Used in Real Recipes

Blanching appears most often in recipes where vegetables must cook quickly, evenly, or predictably during the final stage.

It is rarely the featured technique. Instead, it supports other cooking methods by preparing ingredients in advance.

Blanching commonly appears in:

- Stir-fries where vegetables need to heat through rapidly without releasing excess moisture or overcooking

- Pasta dishes where vegetables are added near the end and must match the pasta’s timing.

- Warm and cold salads using green beans, asparagus, sugar snap peas, or snow peas

- Vegetable purées and soups where color and clean flavor matter more than deep browning

- Freezer preparation for seasonal vegetables that need stability and quality retention

In these dishes, blanching allows vegetables to finish cooking gently instead of being forced to catch up under high heat.

Blanching is also foundational in broader cooking systems, not just individual recipes.

It’s frequently used in:

- French and classical cooking as part of standard vegetable preparation

- Asian cooking traditions, where fast cooking depends on ingredients being pre-adjusted

- Restaurant mise en place to ensure speed, consistency, and portion control

- Make-ahead and batch cooking, where vegetables must hold their texture and color over time

In many recipes, blanching happens before the visible cooking begins. It may not appear dramatic on the plate, but it quietly determines how vegetables behave once heat, fat, and seasoning are applied.

Understanding where blanching appears helps cooks recognize its purpose — not as an extra step, but as a tool for consistency and control.

How to Apply It at Home

Blanching works best when it’s guided by observation, not the clock. Vegetables rarely behave identically, even when cut the same way or cooked together.

Learning what to notice — and how to respond — is what turns blanching into a reliable tool instead of a rigid rule.

What to Notice

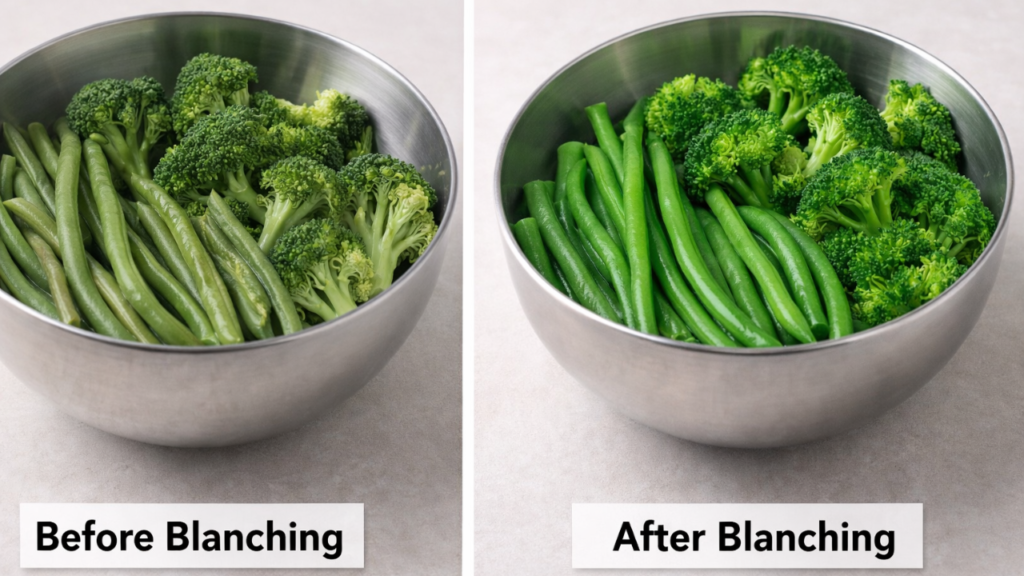

Visual and aromatic changes happen quickly during blanching and provide the clearest signals.

- Color shifts from dull or matte to brighter and more vivid.

- Green vegetables become more vibrant before fading.

- Surfaces appear slightly relaxed rather than rigid.

- Sharp raw aromas soften into a cleaner, lightly cooked smell.

Once color peaks, the useful window is short. Past that point, quality begins to decline.

What to Feel

Touch confirms what sight suggests.

- The exterior should yield gently when pressed.

- The vegetable should bend slightly rather than snap.

- The center should still feel firm and structured.

If the vegetable collapses easily or feels limp, it has moved beyond preparation and into overcooking.

How to Respond

Blanching requires active attention at the moment change occurs.

- Stop cooking as soon as the desired color and softness appear.

- Prevent carryover heat from continuing the cooking.

- Evaluate texture after cooling, not while hot.

Blanching should leave vegetables stable, not fragile. They should hold their shape, tolerate handling, and respond well to the next cooking method.

Think of blanching as setting the ingredient’s baseline — establishing how it will behave later — rather than trying to achieve a finished result.

The goal is vegetables that are ready to perform, not ready to serve.

Common Mistakes & Misconceptions

Many problems with blanching don’t come from poor execution — they come from misunderstanding its purpose.

Blanching is often treated as a cooking method, when it’s actually a preparation tool. That confusion leads to overcooking, loss of texture, and unnecessary steps.

| Misunderstanding | Why It Happens | Better Understanding |

| “Blanching fully cooks vegetables” | Confusion with boiling | Blanching only initiates cooking |

| “Longer blanching is safer” | Fear of undercooking | Excess heat weakens structure |

| Excess heat weakens the structure | Convenience or impatience | Cooling stops carryover cooking |

| “Blanching washes away flavor” | Visible contact with water | Proper blanching clarifies flavor |

| “All vegetables blanch the same way” | One-size-fits-all thinking | Density and structure determine response |

Why These Mistakes Are Common

Blanching looks deceptively simple. Because it uses boiling water, many cooks assume it follows the same logic as boiling pasta or vegetables for doneness.

But blanching operates on transition, not completion.

Most errors happen when cooks focus on time rather than change — waiting longer rather than responding sooner.

Clarifying the Most Common Misunderstandings

- Blanching is not about safety or doneness.

It’s about altering how the ingredient behaves later. Vegetables will still require further cooking. - More time does not mean better results

Once structural change occurs, additional heat only causes breakdown. - Cooling is not a preference — it’s a control step

Without stopping the heat, blanching continues unintentionally. - Flavor loss comes from overexposure, not the water itself

Brief blanching reduces harshness and improves flavor clarity rather than diluting it. - Vegetables respond differently to heat.

Tender greens, dense roots, and fibrous stalks do not soften at the same rate or in the same way.

Understanding these distinctions helps cooks make better decisions rather than blindly following the blanching method.

When blanching is treated as a tool — not a rule — it becomes predictable, flexible, and far more useful in everyday cooking.

Visual or Technical Breakdown

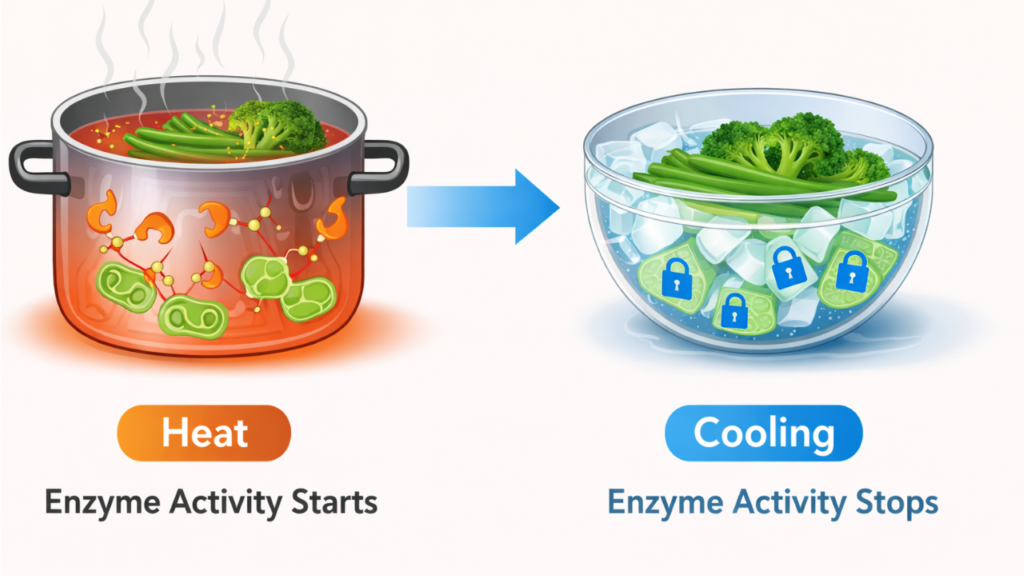

Understanding what blanching changes inside vegetables helps explain why timing and stopping the heat matter so much.

This isn’t about memorizing food science. It’s about recognizing what heat is doing beneath the surface.

What Blanching Changes Inside Vegetables

When vegetables are exposed to boiling water, several quick changes occur:

- Cell walls begin to relax.

Heat softens the rigid plant structure, allowing vegetables to bend rather than snap. - Enzymes responsible for color loss are deactivated

These naturally occurring enzymes continue working even after harvest. Brief high heat slows or stops their activity. - Pigments become more visible before breaking down.

Green vegetables appear brighter as chlorophyll becomes more pronounced — but prolonged heat eventually damages it.

This is why vegetables look most vibrant at a specific moment, then quickly dull if cooking continues.

Blanching captures that peak.

Blanching vs Boiling

Although both use hot water, the intent and outcome are different.

Blanching

- Short exposure to intense heat

- Cooking is deliberately interrupted.

- Structure is adjusted, not completed.

- Color and texture are preserved.

Boiling

- Continuous heat until fully cooked

- Structural breakdown continues

- Texture softens progressively

- Color often fades over time.

The key difference is control.

Blanching applies heat just long enough to create a change, then stops it before damage begins.

That distinction explains why blanching supports brightness, structure, and consistency — while boiling prioritizes softness and doneness.

| Aspect | Blanching | Boiling |

| Purpose | Prepare ingredients for later cooking | Cook food until done |

| Heat exposure | Very brief | Continuous |

| Cooking goal | Structural change, not doneness | Full tenderness |

| Effect on texture | Preserves structure and snap | Progressively softens |

| Effect on color | Enhances brightness when stopped early | Often dulls with time |

| Control level | High — cooking is intentionally halted | Lower — heat continues |

| Typical use | Prep before sautéing, roasting, freezing | Final cooking method |

When to Break the Rule

Blanching is a useful tool, but it isn’t mandatory in every situation. Knowing when not to use it is part of cooking with intention.

Blanching adds value when structure, color, and timing need to be controlled. When those factors don’t matter, the step can be unnecessary.

You may skip blanching when:

- Vegetables are being slow-roasted

Extended dry heat will gradually and evenly soften the structure on its own. - Long braising or simmering is involved.

Moist heat, over time, fully breaks down fibers, making preliminary softening redundant. - Raw texture is the goal.

Slaws, shaved salads, and crisp garnishes rely on snap and freshness, not softened structure. - Delicate herbs or tender greens are used.

Ingredients like basil, arugula, or baby spinach wilt almost instantly with heat and don’t benefit from pre-cooking.

In these cases, blanching doesn’t improve the final result—it just adds an extra step.

Good cooking judgment means choosing techniques based on outcome, not habit.

When blanching improves control, it earns its place.

When it doesn’t, skipping it is the more skilled decision.

Quick Takeaways

- Blanching is controlled, partial cooking — not doneness.

- It improves color, texture, and clarity of flavor.

- It prepares vegetables to cook better later.

- Visual and tactile cues matter more than timing alone.

- Used correctly, it increases consistency and confidence.

FAQs

Is blanching the same as parboiling?

They are similar but not identical. Parboiling usually involves longer partial cooking. Blanching is shorter and always followed by stopping the cooking immediately. Blanching focuses on preparation, not early doneness.

Do I always need ice water?

What matters is stopping the heat. Ice water is the most reliable way to quickly halt cooking. Without rapid cooling, vegetables continue to soften from residual heat. If cooking doesn’t stop, blanching loses its purpose.

Does blanching remove nutrients?

When done briefly, nutrient loss is minimal. Most loss happens from prolonged heat or over-blanching. Short exposure followed by quick cooling preserves overall quality.

Can blanching be done ahead of time?

Yes. Blanching is commonly used as a prep step so vegetables finish faster and more predictably later. This is standard practice in professional kitchens.

Why do chefs blanch so often?

Because it creates control. Blanching improves timing, consistency, and texture — especially when multiple components must finish together.

Final Thoughts

Blanching isn’t about adding extra steps. It’s about understanding how heat affects vegetables and using that knowledge intentionally. Once you see blanching as preparation rather than cooking, it becomes a practical way to improve color, texture, and timing — without guessing.

Explore related Kitchen Know How articles to deepen your technique and cook with clearer control.